礼儀作法

Reigi Sahō − L'étiquette de notre école

Ti, the indigenous martial art from Okinawa, has a set of etiquette based on unique customs and traditions. This etiquette as taught by Onaga Yoshimitsu Kaichō is not a list of rules but part of a living tradition. In his book Shinjinbukan Training Manual Volume 1, published in 2009, Onaga Kaichō refers to these customs as “Ryūkyū no Ti no Reigi Sahō”(琉球の手の礼儀作法), which means “The set of etiquette of Ryūkyū Ti”.

Écrit par Jimmy Mora

Traduit par Ludovic Soler

A famous Karate teacher and his students were trying to climb over a wall. The teacher ordered his students to lift him up to the top of the wall. Once there, the teacher stepped on his students as they were trying to scale the wall. The students were left behind and never reached the other side.

Another teacher climbed to the top of a wall and stretched his hand down toward his young deshi (disciple) to help him climb over. Years later the deshi was able to lift up the teacher to the top of even higher walls, and the teacher always continued to reach down for his deshi. Finally, at an old age the teacher reached the top of the highest wall for the last time and helped his deshi jump to the other side, thus bringing the knowledge of Ti to the next generation. Today, the deshi has become a Tichikayā (practitioner of Ti).

This tale paraphrases one of the many stories told by Onaga Yoshimitsu Kaichō. Nowadays, many instructors are like the first teacher in the story. In such an environment, the senpai (senior) demands strict adherence to etiquette and rules just to control the kōhai (junior members). This approach only hinders students from developing further and surpassing their teachers.

On the other hand, the second teacher in the story empowered his deshi to reach out, grasp for knowledge and climb over the wall. The process of Ti is the opposite of karate: knowledge is not trickled down from teacher to student but increased with each generation. The practice of Ti in Okinawa is in danger of extinction as most schools follow the path of sports Karate. Onaga Yoshimitsu Kaichō is a Tichikayā who understands “Ryūkyū no Ti no Reigi Sahō” as part of a living tradition and not as meaningless rules.

This article presents the following topics:

The etiquette of the Ryūkyū Bushi

The Shomen and the Dōjō floor layout

Physical space in relation to others

Tichikayā Rei (Bowing used by the practitioners of Ti)

Rei from Seiza position (Bowing from the formal sitting position)

Verbal and non-verbal communication

The impolite expression “Osu” (or “Oss”)

Etymology of Reigi Sahō

The term “Reigi Sahō”(礼儀作法) combines two separate words:

−(礼儀)Reigi: manners, courtesy and etiquette.

−(作法)Sahō: manners, etiquette and propriety, or the manner in which something is done.

As the term reigi sahō combines two words with similar meaning, a deeper understanding of reigi sahō emerges, going beyond simply good manners. Instead it refers to “a complete set of manners, courtesy and etiquette used by individuals and society in general”.

In order to define reigi sahō from a martial arts perspective, perhaps it is better to avoid stereotypes such as “discipline”, “respect”, “militaristic”, “natural”, etc. For some people the meaning of “militaristic”, for example, is illustrated by the stereotype of a Karate school full of people screaming “Osu” after every command or hitting each other endlessly without precision.

On the other hand, being “militaristic” could have the opposite meaning for those who actually served in the military, because for those people being “militaristic” means to train in silence, in the dark, using fast and deadly techniques – “one shot, one kill”, as opposed to sports kumite: “many shots, but no kills”. In the military this concept is known as “swift, silent, deadly”, and it parallels with some concepts used to train Ti, such as “shizuka, hayaku, seikaku” (silent, fast and accurate). Those who are true Tichikayā train mostly in the dark without using any “kiai” or heavy breathing. The Tichikayā also train machiwara in order to develop a hand strike capable of delivering a deeper and more accurate kinetic force.

The etiquette of the Ryūkyū Bushi

The development of budō (martial arts) around the world has been closely associated to the warrior class in each culture. In the same way, the customs of etiquette associated to the practice of Ti in Okinawa are directly connected to the Ryūkyū Bushi (Ryūkyū warrior), who established their own culture and traditions. Thus we can speak of a Ryūkyū tradition of martial arts culture: “Ryūkyū Koyū no Budō Bunka”(琉球固有の武道文化). In this way reigi sahō associated to the practice of Ti is an outer expression of a martial arts culture.

Practical application:

1) Reigi sahō is applied at all times, i.e. during training, inside and outside of the Dōjō, as well as during social occasions.

2) The ability to apply reigi sahō is a reflection of Busai (martial arts age).

3) In the Shinjinbukan School these traditions are known as “Ryūkyū no Ti no Reigi Sahō”(琉球の手の礼儀作法) or “The set of etiquette of Ryūkyū Ti”.

4) The etiquette of Ryūkyū Ti is not taught for the sake of tradition; it has practical martial arts applications and philosophical value.

5) The customs and traditions of Ryūkyū Ti should reflect one’s heart and not focus on the external expression of each ceremony or custom.

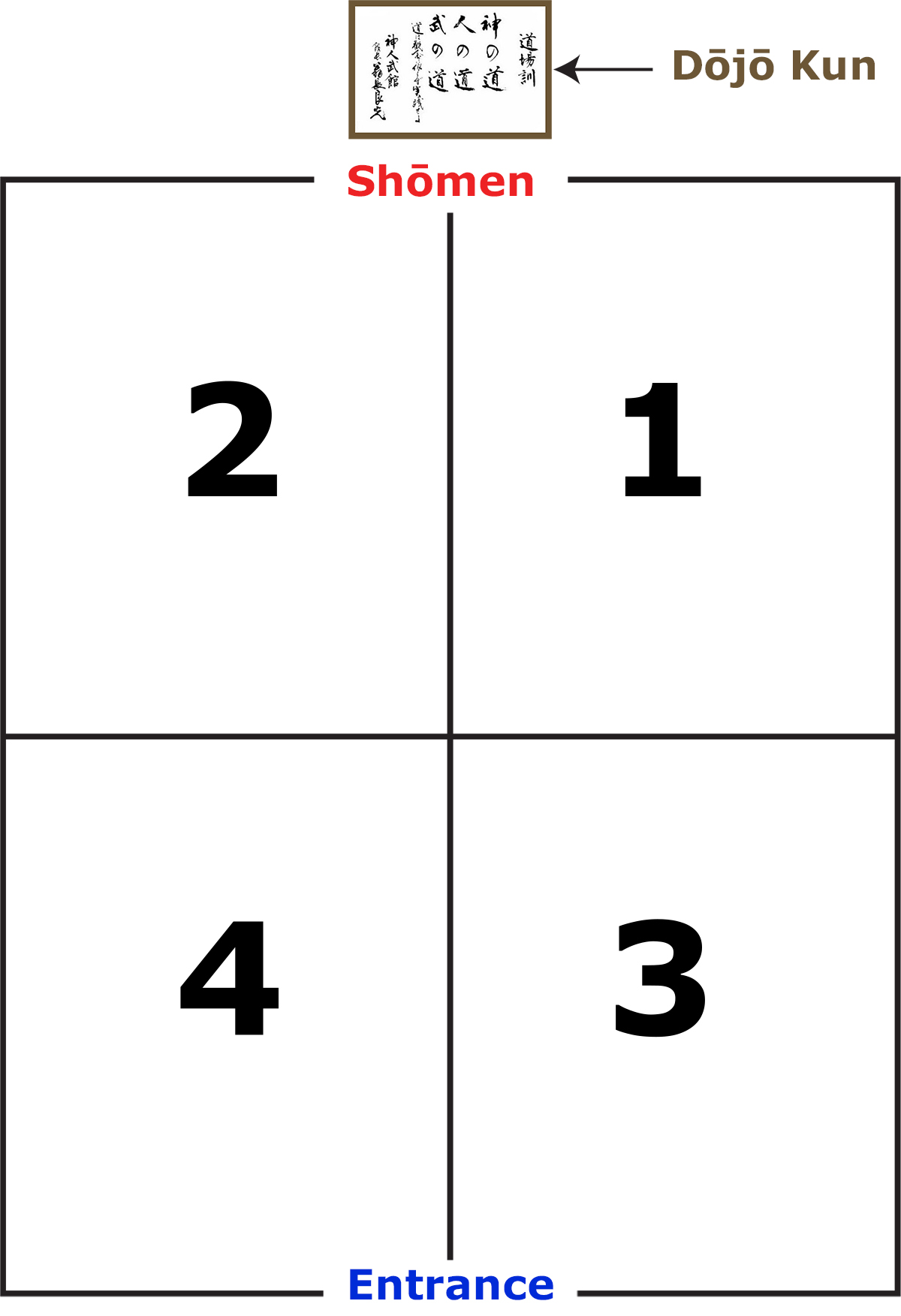

The Shomen and the Dōjō floor layout

The shomen(正面) is the front area of a Dōjō where an altar is commonly placed, and it is considered the place of highest honor. In Japan, small altars are found not only in a Dōjō but also in homes, offices, stores, etc. In the Okinawan tradition, it is more typical to find an altar dedicated to ancestor worship. The types of altar listed below are associated to a specific tradition or ritual, e.g. Shinto, Buddhism, ancestor worship, etc.

−(上座)Kamiza

−(佛壇 or 仏壇)Butsudan

−(神棚)Kamidana

−(神座)Shinza

A new tradition was established by Onaga Yoshimitsu Kaichō by only placing the calligraphy with the Dōjō Kun (precepts) and keeping the shomen area empty without any altars or pictures of the deceased teachers.

The shomen is normally aligned towards the east as the point of reference to divide the Dōjō into four areas assigned by seniority. See the image below.

Section 1 – Front right area near the Dōjō Kun used by the Sensei.

Section 2 – Front left area near the Dōjō Kun used by the senpai.

Section 3 – Back right area used by mid-level students.

Section 4 – Back left area used by the most junior students.

Practical application:

1) Students learn to identify by themselves and use their assigned training area inside the Dōjō.

2) When the teacher or senpai instructs a group during a drill or Kata, the students line up by seniority following the floor layout.

3) When the Sensei or senpai invites a student to train in section 1 or 2, it is for a short individual session.

Afterwards, the student should return to his individual training area (sections 3 and 4).

4) In some cases, when a guest visits the Dōjō they are offered to use section 2.

5) The placement of the machiwara, sagi machiwara, and other training tools follow the floor layout.

Physical space in relation to others

For a Tichikayā, the practice of reigi sahō also requires an awareness of our physical space and surroundings at all times – e.g. our position in relation to our teacher, senpai, training partners, or a potential attacker.

When the teacher sits down to give instruction, the student remains at a lower height than the teacher. This setting shows that we must humble ourselves in order to receive knowledge. From a western or modern perspective this concept may be perceived as “submissive”. However, if we were in the desert dying from thirst, would we place our cup above the water fountain where it could not be filled?

Another example of using space is when the students re-learn how to walk and take steps without making unnecessary noise or clumsy movements. How should we move our body? How should we walk? What is the proper way to sit down or stand up? The answers to these questions lead us inexorably towards Tenshin.

In terms of Ti, the student’s true Busai (martial age) and understanding of reigi sahō is reflected by the simple action of walking across the Dōjō and sitting on seiza noiselessly and gracefully.

As Onaga Kaichō teaches, “Ti wa Chie desu”(手は知恵です) or “Ti is wisdom”. If we are thirsty for knowledge, we must “lower our cup” in order to fill it with “wisdom”. Therefore, the level of reigi sahō is a reflection of one’s understanding of this wisdom.

Practical application:

1) When going up a stairway, walk behind the teacher in order to remain at a lower height.

2) When going down a stairway, walk in front of the teacher in order to remain at a lower height.

3) When Sensei sits down to speak to the students, sit in seiza (on your knees) and wait to be told to sit in a relax manner (crossed legs). Do not stand in from of him and remain at higher level. This would not apply if the teacher is sitting while the student is training.

4) When the teacher or senpai instructs a group during a drill or Kata, the students will line up by seniority following the floor layout.

5) When the teacher or senpai invites a junior student to train at the front of the Dōjō (sections 1 or 2), normally it is only for a short individual session. Afterwards, the student should return to his individual area (sections 3 and 4).

6) Students learn how to walk without making noise on every step. The objective is to understand how to use your body weight on every step.

7) Students learn how to pick up and move object with their hand. Therefore, it is considered disrespectful to touch any tools or any objects with your feet.

8) When sitting on the floor. Avoid stretching your legs and showing the bottom of your feet towards Sensei or towards the shomen area.

Tichikayā Rei (Bowing used by the practitioners of Ti)

A martial artist (bushi) must train to be ready to engage an opponent at any time. The motion of crouching low and bowing are in essence the same, as a low stance enables our body to attack like a tiger and be less exposed to surprise attacks. The Tichikayā bow is executed from a Jigotai or Sanchin stance. As the body is lowered, the hands cover the inner thigh, the body rotates from the hip and the back is kept straight without extending the chin.

Practical application:

1) Bow as one enters and exits the Nā (training area).

2) Bow as training partners approach each other before Kakie.

3) Bow as training partners move away from each other after Kakie,

4) Bow as one enters and exits the Nā around the Machiwara or Sagi Machiwara.

Rei from seiza position (Bowing from the formal sitting position)

The rei from seiza position, or formal sitting position, is only used indoors and never outdoors. Bowing from seiza is not made towards the teacher or an object, but for ourselves, asking for wisdom and self-improvement with a humble heart. The seiza position is commonly associated to Zen meditation. However, Zen meditation, or Mokusō(黙想), a typical meditation used in traditional Japanese martial arts are not a part of Shinjinbukan School or Ti.

Our Ti is based on self-improvement through training and not through contemplation. In the Shinjinbukan School, seiza is an “active physical exercise used for awareness” and not a “passive meditation” in search of mystical answers. For example, during Seiriundō at the end of each class, the eyes are focused on one point without blinking or closing them or without letting the mind wander into space. This exercise develops concentration, body alignment, as well as breath and eye control. For more details, see: The philosophy of Ti

Practical application:

1) At the beginning of training, as each person enters the Dōjō, sit in Seiza and bow individually and never as a group. During the bow, say: “Onegai Shimasu”.

2) At the end of training, as each person leaves the Dōjō, sit in Seiza and bow individually and never as a group. During the bow, say: “Arigatō Gozaimashita”.

3) The correct Seiza form is executed without making noise. Do not drop the body to the floor and maintain a straight axis as you sit down and get back up.

Sōji (Cleaning the Dōjō)

The word “soji” means to clean. In a traditional Dōjō cleanliness is extremely important. Hence, soji is done at the end of each class or any time when the Dōjō needs to be cleaned. Since, Okinawa is very hot and humid there is a real need to regularly wipe off all the sweat from the floor. In other traditions there is also a lot emphasis on cleaning one’s weapon, training tools, body - e.g. sword, spear, knife, gun, etc. Even in a gym there are signs asking people to clean each weight machine after use.

Practical application:

1) Use a small damp hand towel to wipe off the floor. Sit on a low squatting position and clean the floor.

2) Take initiative and begin cleaning without being told by a senpai.

Personal hygiene

Since the weather in Okinawa is sub-tropical with only two seasons, personal hygiene is very important. The Tichikayā do not wear much clothing during training, often just shorts and no t-shirts, and they use “touch” for understanding the correct body position and mechanics.

Practical application:

1) During long training sessions, the teacher will give the command “Ase fuitte” or “Ase fukinasai”, which means to dry the sweat off your body. Use a small hand towel to clean your body during these short pauses.

2) Exit the Nā (training area) to dry your sweat, and sit in low stance called Sonkyo. Make a Tichikayā bow before exiting and upon returning to the Nā.

Verbal and non-verbal communication

In Japanese culture, there are several levels of politeness used to make a request and express gratitude. In the martial arts culture, there is an even more complex ritual to communicate with other people. There are too many examples, but the situations listed below are perhaps the most essential.

Practical application:

1) Before training say “Onegai shimasu”, which is the polite form to say please, but the implied meaning is “please teach me”.

2) After training say “Arigatō gozaimashita”, which is the polite form to say thank you, but the implied meaning is “thanks for teaching me”.

3) When answering a direct question from the teacher or a senpai, answer “hai” (yes) or “ie” (no), spoken with confidence and without screaming.

4) When a command or specific instructions are given to a student, then the most appropriate answer is “hai, wakarimashita” (yes, I understood).

5) It is considered rude to point at people and objects, especially in the Dōjō.

6) Use your hands to move an object lying on the floor. It is considered disrespectful to use your feet to move any object – e.g. chishi or any other tool.

The impolite expression “Osu” (or “Oss”)

The expression “Osu” (or “Oss”) is not part of the indigenous Karate culture of Okinawa and is not used by most Japanese native speakers in everyday life. Unfortunately, many practitioners of sports karate worldwide have adopted the exaggerated use of “Osu”. It originated in some boot camp trainings, military and police academies, but it is not used in normal conversations among Japanese military or law enforcement officers.

Practical application:

1) When speaking to native Japanese speakers avoid saying “Osu” or “Oss” after every sentence.

2) Avoid saying “Osu” or “Oss” in a traditional Okinawan Dōjō. It would be considered extremely rude or insulting, especially at any Shinjinbukan Dōjō.

Toasting and table manners

Reigi sahō is also applied during social occasions, and students must also demonstrate good table manners and a basic understanding of the relationship between Senpai and Kōhai. From a cultural perspective, it is essential to develop a basic knowledge of the culture and cuisine of Okinawa and Japan – e.g., when to start eating, how to use ohashi (chopsticks) and how to serve sake, awamori, tea, etc.

Practical application:

1) When toasting with Sensei or your Senpai stretch your arms without bending your elbows and hold the cup with two hands. Wait to be told there is a toast. Do not offer a toast to Sensei.

2) When serving a drink, the arms are stretched out without bending the elbows. The bottle is always oriented sideways without pointing to the person being served, i.e. Sensei or Senpai.

3) Be careful when putting the cup down. If you strike the table with your glass and make noise, this is interpreted in the Tichikayā culture as asking for a fight.

4) Do not start before Sensei tells you to eat. Even if other people tell you, only start eating and drinking when Sensei says to begin.

Conclusions

The origin of the Ryūkyū warrior culture goes back to the time of the Anji or Aji, the warrior chiefs (ca. 900 to 1,000 ad.), and continued through the formation of three kingdoms (Chūzan, Nanzan and Hokuzan) and the establishment of the Ryūkyū kingdom by King Shō Hashi in 1429. The development of the Ryūkyū martial arts culture continued its evolution and was also influenced by China and Japan. This evolution continued from the time of the Satsuma invasion (1609) until the annexation of Okinawa to Japan during the Meiji era (1879).

For Onaga Yoshimitsu Kaichō, Ti is not about competitions, karate tournaments, gold, silver or bronze medals. Instead, Ti is about how not to lose one’s life. Reigi sahō is part of the training of Ryūkyū no Ti. The study of Ti is deeper than learning how to apply fighting techniques. The Tichikayā who already holds the knowledge of Ti, is constantly lowering his/her cup to be filled from the fountain of wisdom. Thus, for the practice of reigi sahō is part of this learning process.

© 2013 Shinjinbukan France Copyright